Who is Peter Mandelson? The New Labour Architect Explained

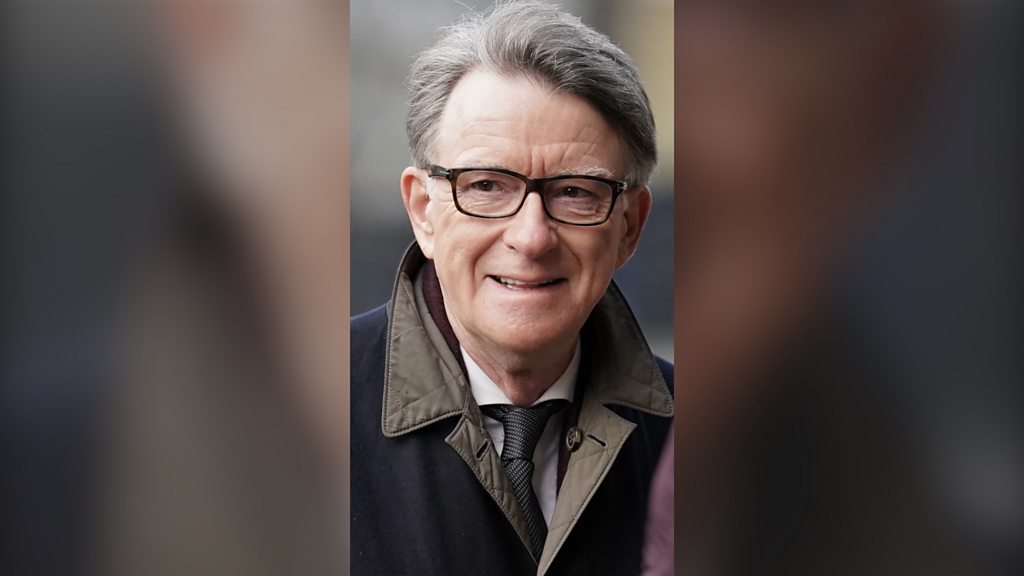

Who is Peter Mandelson?Image Credit: BBC Politics

Key Points

- •BBC Politics

- •Key Role: As Director of Communications, he professionalised the party's media operations, pioneering the "rapid rebuttal" unit and ensuring disciplined, on-message communication that ultimately helped secure the landslide 1997 election victory.

- •Political Philosophy: Mandelson championed the "Third Way," a political ideology that sought to blend right-wing economic policies (such as market liberalisation) with left-wing social values. This remains central to his thinking.

- •First Resignation (1998): Mandelson resigned as Trade Secretary after it was revealed he had accepted an undeclared interest-free loan of £373,000 from fellow minister Geoffrey Robinson to buy a house in Notting Hill. While he was later cleared of any impropriety, the failure to declare the loan was deemed a breach of the ministerial code.

- •Second Resignation (2001): After being brought back as Northern Ireland Secretary, a role in which he was widely praised for his work on the peace process, he was forced to resign again. This followed accusations that he had intervened in a passport application for Srichand Hinduja, an Indian businessman whose company was a key sponsor of the Millennium Dome. An independent inquiry later cleared him of acting improperly.

Who is Peter Mandelson?

BBC Politics Copyright 2026 BBC. All rights reserved. The BBC is not responsible for the content of external sites. Read about our approach to external linking.

Dubbed the "Prince of Darkness" for his mastery of political strategy, Lord Peter Mandelson has once again emerged from the shadows to become a pivotal, if unofficial, adviser to the current government. For a new generation, his name may be known only through Westminster legend, but his influence on British politics and economic policy over three decades is undeniable. Understanding who he is, and what he represents, is crucial to understanding the government's current trajectory.

Mandelson’s career is a study in power, resilience, and reinvention. A key architect of the "New Labour" project that brought Tony Blair to power in 1997, he has served at the highest levels of British and European politics, been forced to resign twice in disgrace, and returned twice to the heart of government. Now, his voice is again shaping policy, particularly on business and international trade.

The Architect of New Labour

Peter Mandelson’s political journey began not in Parliament, but behind the scenes. As the Labour Party's director of communications in the late 1980s and early 1990s, he was instrumental in rebranding the party, shedding its "unelectable" image.

Alongside Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, he formed the triumvirate that forged New Labour—a centrist, pro-market political force designed to win over Middle England. His expertise in media management and strategic messaging was considered unparalleled, earning him both respect and a reputation for ruthless efficiency.

- Key Role: As Director of Communications, he professionalised the party's media operations, pioneering the "rapid rebuttal" unit and ensuring disciplined, on-message communication that ultimately helped secure the landslide 1997 election victory.

- Political Philosophy: Mandelson championed the "Third Way," a political ideology that sought to blend right-wing economic policies (such as market liberalisation) with left-wing social values. This remains central to his thinking.

A Ministerial Career of Highs and Lows

Elected as the MP for Hartlepool in 1992, Mandelson's rise in government was swift. He was appointed to the Cabinet by Tony Blair, first as Minister without Portfolio to oversee the Millennium Dome, and later as Secretary of State for Trade and Industry. However, his ascent was punctuated by major controversy.

His career is famously defined by two high-profile resignations from the Cabinet, a feat unmatched in modern British politics.

The Resignations

The controversies that led to his departures from government have become defining moments in his political story, cementing his reputation as a divisive and complex figure.

- First Resignation (1998): Mandelson resigned as Trade Secretary after it was revealed he had accepted an undeclared interest-free loan of £373,000 from fellow minister Geoffrey Robinson to buy a house in Notting Hill. While he was later cleared of any impropriety, the failure to declare the loan was deemed a breach of the ministerial code.

- Second Resignation (2001): After being brought back as Northern Ireland Secretary, a role in which he was widely praised for his work on the peace process, he was forced to resign again. This followed accusations that he had intervened in a passport application for Srichand Hinduja, an Indian businessman whose company was a key sponsor of the Millennium Dome. An independent inquiry later cleared him of acting improperly.

The European Stage and a "Third Coming"

After his second resignation, many believed his political career was over. Instead, Mandelson reinvented himself on the European stage. In 2004, he was appointed as the UK's European Commissioner, taking on the powerful Trade portfolio.

In Brussels, he became a formidable figure, known for his sharp intellect and tough negotiating style in global trade talks. His pro-free trade, pro-globalisation stance often put him at odds with more protectionist member states, particularly France.

His career took another dramatic turn in 2008. In a stunning political move, Prime Minister Gordon Brown—his long-time political rival—recalled Mandelson to the British cabinet for a "third coming."

- Role as Business Secretary: Elevated to the House of Lords, he became Lord Mandelson, Secretary of State for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform. He was a central figure in the government's response to the 2008 global financial crisis, overseeing bailouts of the banking and automotive industries.

Life After Westminster: The Business of Influence

After Labour's defeat in the 2010 general election, Mandelson transitioned seamlessly into the private sector. He co-founded the strategic advisory firm Global Counsel, which uses his vast network and political experience to advise multinational corporations on political and regulatory risk.

This move solidified his position as a key link between the worlds of business and politics. His firm provides intelligence and access for companies navigating the complexities of global markets, a role that keeps him deeply connected to economic and policy debates.

The Mandelson Doctrine: Policy and Implications

Today, Lord Mandelson's influence is being felt once more in Downing Street. As an informal adviser, his voice carries immense weight on key policy areas, reflecting his consistent ideological positions.

- Economic Policy: He remains a staunch advocate for fiscal discipline, a pro-business environment, and public-private partnerships. His counsel is seen as a moderating force, pushing the government towards a centrist economic policy designed to reassure international markets and investors.

- Trade and Europe: A committed pro-European, Mandelson has long argued for the closest possible trading relationship with the European Union post-Brexit. His experience as a former EU Trade Commissioner makes his advice on navigating future trade deals highly sought after.

- Political Strategy: His primary value to the current leadership is his strategic brain. He advises on how to manage the media, neutralise political attacks, and maintain the broad coalition of voters needed to hold onto power.

What to Watch

The re-emergence of Peter Mandelson as a key government influencer signals a deliberate strategic choice: to anchor the government firmly in the pro-business, centrist tradition of New Labour.

His proximity to power will continue to be a source of tension within the Labour Party, particularly with those on the left who view his brand of politics with suspicion. For business leaders and international partners, however, his presence is seen as a sign of stability and pragmatism.

The key question is how much a government in 2026, facing vastly different economic and social challenges than those of 1997, will adhere to the Mandelson playbook. His influence on major upcoming decisions—from the next budget to a new trade deal with the EU—will be the ultimate measure of his enduring power.

Source: BBC Politics

Related Articles

Nationwide Protests Against ICE Enforcement Erupt in U.S.

Thousands are protesting ICE after the DOJ declined to investigate a fatal agent-involved shooting in Minneapolis, fueling a national movement and public anger.

Venezuela Amnesty Bill Could Free Political Prisoners

Learn about Venezuela's proposed amnesty bill to release political prisoners. The move could signal a major political shift and affect future economic sanctions

Pokémon Cancels Yasukuni Shrine Event After Backlash

The Pokémon Company has canceled an event at Tokyo's controversial Yasukuni Shrine after facing international backlash from China and South Korea.

US to Lose Measles Elimination Status: What It Means

The U.S. is poised to lose its measles elimination status due to escalating outbreaks. Learn what this downgrade means for public health and the economy.